15/12/12

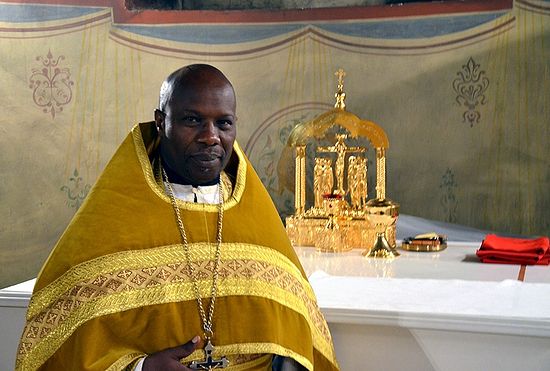

An interview with Fr. Phillip Gatari, an Orthodox priest from Kenya

Fr. Phillip Gatari recently visited Moscow. He was a guest of Sretensky Monastery for two days, and celebrated the Liturgy with the brothers and other visiting monks from Mt. Athos. After the services, this joyful pastor told us about Orthodoxy in Kenya and his work as the principal of a rural school.

Kenya is not a wealthy country, and people live a very simple life here, especially in the provinces. Fr. Phillip, the rector of the Church of St. Anthony in the village of Ishamara in central Kenya, is no exception. He is very busy—Orthodoxy is the most dynamically growing confession in Kenya, and mass baptisms in villages are not a rarity, including as many as fifty to seventy people at once.

—Fr. Phillip, tell us about your church. What ecclesiastical jurisdiction does it belong to?

Our church is dedicated to St. Anthony the Great, who lived in Egypt and is the head of monasticism for the whole world. We belong to the jurisdiction of the Alexandria Patriarchate, and our faith is Orthodoxy. My parish is located in the diocese of Kenya, and we are trying to broaden and increase it. We do not have a large parish—around 300 people, about 100 of them active parishioners.

—How did the Kenyans come to Orthodoxy?

Orthodoxy came about here at the initiative of the local people. They tried to find the true Church. Back in 1932, Orthodox Kenyans wrote a letter to Patriarch Meletios about being received into the Patriarchate of Alexandria; the Patriarch gave them a positive answer, but he soon died. The Kenyans again wrote a letter, this time to Patriarch Christopher. In 1942, Metropolitan Nicholas of Aksum came to us, looked everything over, and in 1946, the Kenyan Church was received into communion with the Patriarchate of Alexandria.

Soon, in Kenya the liberation movement against the colonial regime began. This was in 1952. There were many Orthodox parishes on the side of the rebels, and the Protestant and Catholic priests called the uprising a rebellion of pagans and savages. They imprisoned the Orthodox priests. For example, Fr. George Arthur Kaduna, the first “black” bishop in Kenya, spentten years in prison together with the future president of the country and leader of the Kikuyu tribe, Jomo Kenyatta.

The president left after his death a parcel of land for the building of an Orthodox seminary, which opened its gates in 1982. The current archbishop of Albania, Anastasios, opened this seminary. We began with private classes on weekends, studying only Liturgics, and now the seminary has risen to a serious level; we graduate students with diplomas. So, this is part of our history.

—How did you personally become Orthodox?

I became Orthodox in my childhood, at nine years old. I was not baptized as an infant.

—Are your parents also Orthodox?

They were not believers, but later they followed in their son’s footsteps and became Orthodox.

—What was most significant on your path to Orthodoxy—a person, school, or something else?

Our parish priest. He influenced me, in my village, in our church. I was a child then. I continued to go to church also after growing up.

—Tell us about your church. What is it built of?

At first our church was made of clay, and only later was there a stone building. But we have no iconographers to paint the frescoes, and it is very expensive to hire artists from Europe. Therefore we have only icons that we hang on the wall, but no wall paintings. We also had a bell, but it was stolen right from the tell tower.

—I would like to know about the spiritual life at your parish: how often do people confess and receive Communion?

Those who feel the need and have prepared themselves generally receive Communion whenever there is a Liturgy. But of course, if something prevents them, they do not commune. We usually try to talk with these people and find out what the problem is. Confession before Communion is generally not mandatory. It depends upon the people in particular. If someone comes and says, “I need to confess,” then of course we take his confession. But in many cases I try to send the person to a more experienced priest for confession.

—What kind of missionary work is done in Kenya, in your parish, and in your diocese?

We have many different kinds of missionary work. There are youth programs, programs for women, programs of male brotherhoods. We have Sunday school classes. There are also educational programs directed at work in high school and elementary classes. In the secular schools, we also try to keep a Christian direction.

I am very proud of the fact that there is an Orthodox high school in our parish that was founded by the Church, but we accept all children there, no matter what confession. We work according to a state educational program that is required in all schools in Kenya. This program is used everywhere, even in private schools: the lesson is forty minutes long, there should be eight lessons per day, qualified teachers teach them, and so on. Education is under government control.

Now we have sixty-five students, and this part of our missionary work. I as the director of our school, and the students.

When I was assigned to this parish there was a five-acre parcel of land designated for a school. It had been abandoned over the course of ten years, there was nothing there; no building, nothing. Now with God’s help there is a school there, with classrooms and desks.

In the church we try to use the local languages. Sermons are also in the local language. But in the schools, English is used throughout Kenya. The entire population speaks English.

—In your opinion, does Orthodoxy have a larger future in Kenya?

If we have wise governance and we rely upon the local peoples, follow their needs, and be their partners, then we have great potential. Our mission must encompass new ethnic groups.